Welcome back to A View from The Summit. The Summit Academy is a classical liberal-arts school rooted in the Catholic tradition, located in historic Fredericksburg, Va., serving students in grades 6-12. This newsletter informs readers about our school and the ways in which it is helping renew education and the Church.

Thank you to our faithful readers, occasional readers, and new subscribers. This newsletter is great fun to produce, and it continues to bring value to this community, and communities beyond. There will be two more Tuesday newsletters in May, then summer will see occasional new editions of A View from The Summit. The regular schedule will return in September 2024, after our next academic year is underway.

Administrative Review:

As the academic year comes to a close, we have several highlight events upcoming that we have been hard at work arranging: senior thesis finals, field day, and our senior outdoor trip to Moab.

Senior thesis finalists will defend their papers to a panel of guest judges on the evening of May 9. Also on May 9 is field day, when we will head to our 15-acre property for competitions, dunk-tanking, and more fun. The capstone Outdoor Program trip for our seniors will take place after that, and our seniors will go backpacking in Moab, Utah. Ms. Genevieve Riley—math instructor, soccer coach, and Outdoor Program director—is leading this special trip.

Otherwise, the administrative leadership team is busy knocking out priority items for the end of this year, summer, and the beginning of next. With the help of our new organizational tool Trello, the team is: Making admissions decisions, welcoming new parents, reviewing scholarship essays and scheduling interviews, continuing student formation, overseeing house competitions, organizing upcoming events, initiating summer planning, renewing contracts, and launching our first-ever 403b retirement plan offering for employees.

These and other developments are essential for building the school’s culture, especially as a great place to work.

From my classroom

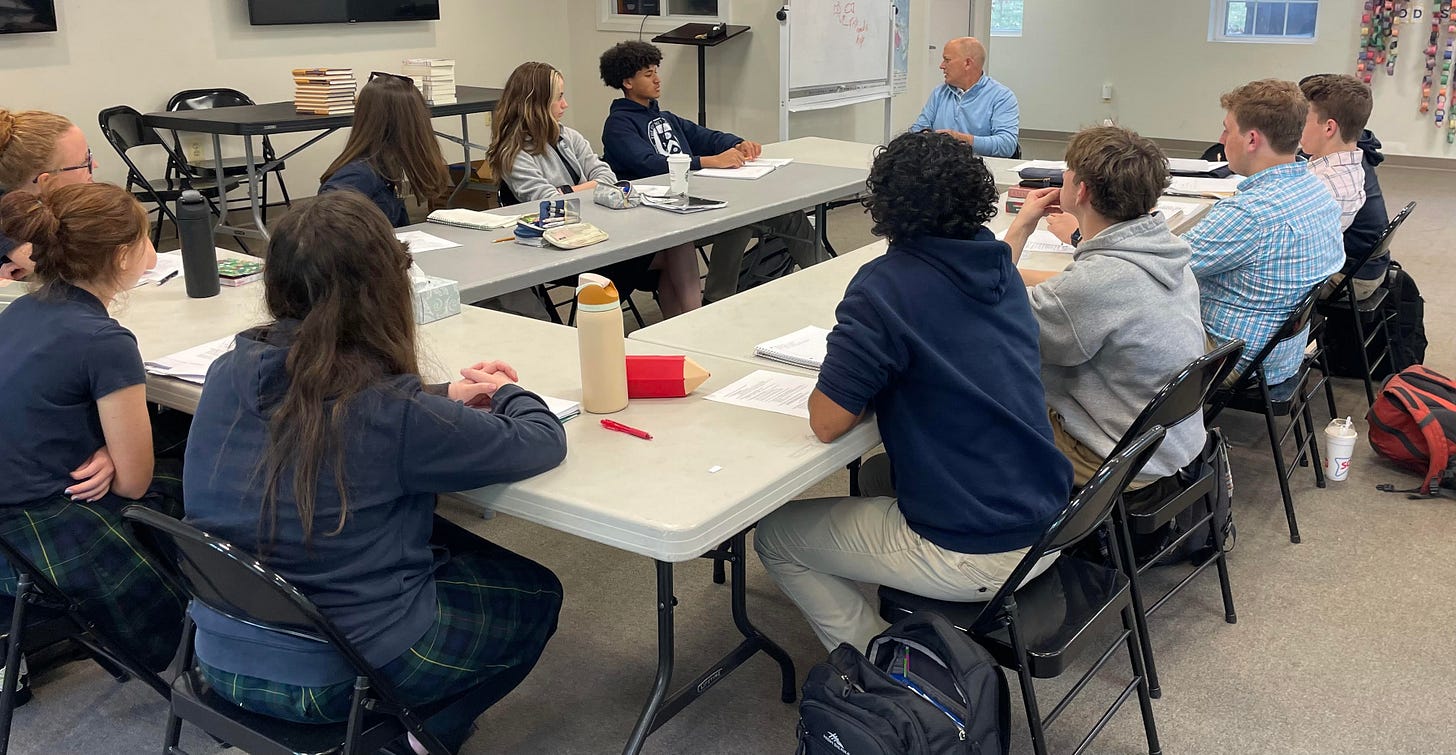

Last Friday, my class welcomed the CEO of Shore United Bank, Jimmy Burke, as a guest lecturer. Shore United has more than 40 locations and manages more than 6 billion dollars. Burke sets the bank’s vision, manages top executives, and trusts his leadership to execute on that vision, providing them with daily support.

Jimmy is passionate about Catholic education. He was discerning the priesthood before he got a summer job, met his soon-to-be wife, and found his way into banking. “It’s funny how God works,” Burke remarked about his vocational path. In just over an hour, Burke shared with students how he found his way from discerning the priesthood to running a bank, how he never stops learning by reading 40-50 books per year, and the value of finding one’s vocation founded on love and self-sacrifice. He answered questions about everything from the gold standard to financial crimes, credit scores, and his daily habits.

Burke gifted each student new copies of two books:

Who Not How: The Formula to Achieve Bigger Goals Through Accelerating Teamwork by Dan Sullivan and Benjamin Hardy, which admonishes readers to think about problems in terms of “Who will help me solve this?” rather than “How can I solve this?” Burke impressed the importance of collaboration and cooperation in achieving ambitions.

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance by Angela Duckworth, which highlights the importance of determination and consistent effort in achieving results. It’s not intelligence, talent, or looks that wins the day, argues Duckworth with a series of real-world studies to back her up. It’s grit—that ability to work consistently and tirelessly towards a goal.

Board Interview:

This new section highlights the experience, insights, and passion of one Summit board member. This week, I interviewed Joseph Stibora. Dr. Stibora has served on the board for five years and in his current role as chairman for the last two. He has an impressive background in Catholic education, having earned a B.A. in philosophy from the University of St. Thomas and a Ph.D. in political philosophy from the University of Dallas. Dr. Stibora and his wife Carrie have five children.

Q: What inspired you to serve on the Board of Directors?

A: My wife was invited to be the Summit’s first graduation speaker in 2017. As I learned about the school, I realized that I very much wanted it to succeed because I was looking for a good high school option in the region, even though my children were only in elementary school.

When Julian invited my wife to serve on the board, she declined and said, “The one you really want is my husband.” And it’s history from there. After talking to Julian and getting an idea of their plans and what they had hoped for, I realized that this was absolutely what I wanted to flourish in Fredericksburg, both for the community and for my family. I wanted to do what I could to make sure that the school thrived, so I agreed to serve.

Q: What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced as a board member, and how did you overcome it?

Organizations are a bit like people: as they mature, they invariably go through natural growing pains. And for organizations, one of the most acute is the transition from being a founder-run institution to being led by a board. The fact that it is perfectly normal, however, doesn’t mitigate the difficulty. I think we came out of the challenge stronger than ever because of three things. First, we began asking for the intercession of Our Lady, Undoer of Knots and of our own late saint Santiago Reyes. Second, the board members stayed in constant communication with each other and sought wise counsel from outsiders who were able to speak from experience. Third, we revamped the board and expanded its membership to include new perspectives and voices. Nobody likes growing pains, but I am truly grateful that we went through them. We are in a significantly better position today than I could have imagined just a year ago.

There is one other major challenge that might be worth mentioning because it has had such a dramatic impact on the school: Covid. The challenge I’m thinking about, however, wasn’t so much the disease as the opportunity it created for us to start the middle school. When Covid hit, parents with middle school-aged children started beating down our door to help them. The board had previously discussed the possibility of a middle school, but we had only thought of it as something on about a five-year horizon. But with Covid, we had the community we are serving tell us that they need us . . . now.

The key for us to move forward was, first, a deep commitment by the board that we are partners with the parents. If they have a pressing need that we could answer, it was our duty to try. Second, we organized a couple open fora with the parents to learn what they really wanted and how, given our limited faculty and classroom space, we could creatively respond. We have come a long way in the few years since we reworked the schedule to tuck three new grades into an already full facility and introduced the limited hybrid program. I could not be more proud of the faculty and staff who went the extra mile to educate these new students, and of the parents who were so supportive and patient as we worked with them. Now, I have a hard time even imagining the Summit without a middle school.

Q: Tell me about the mission and its preservation. How important is that to you?

In a nutshell, we’re committed to classical Catholic education. That means mind, body, and spirit, which translates into academics, sports and outdoor activities, and the faith. Together, these three form a well-rounded education in virtue. That’s what we’re after. I’m fully committed to this way of education in terms of what is necessary to raise sons and daughters of the Church.

So our education can’t be one-sided, just focused on academics or on sports. God made us as incarnate spirits, so it’s our fundamental duty to cultivate them as best as we can. It’s no easy task to balance competing priorities against each other, and even harder when you throw in planning for the school’s anticipated continued growth. Sometimes–when I step back from the frustratingly futile attempts to bi-locate as my wife and I juggle pick-ups and drop-offs for games, practices, plays and all the other things that my kids are doing–the situation strikes me as almost comical. We have sports teams but no sports facilities (of our own, yet). We’re a Catholic school in a Baptist church! I try not to let the daily grind distract me from gratitude for our heroic accomplishments.

I have also come to be grateful for some of the challenges because of the unexpected benefits that have arisen because of our less-than-ideal circumstances. For example, our school takes its name from the Blessed Sacrament, but we are only occasionally able to have school masses. As much as I long for the day when we can have daily mass at school, I am ecstatic that the students pray the Divine Office at the beginning of each day. This is a wonderful habit to develop, and I seriously doubt that many would be doing it if we had the mass. So I think our solution to a challenging situation has had an incredible benefit for the cultivation of a life of prayer.

Q: Now let’s humanize “The Board.” What’s your hobby, favorite book, or favorite sports team–and why?

A: I’m a foodie, and I really enjoy cooking. Cooking and experimenting with food is probably my favorite pastime. I like the opportunity for creativity (even if, sometimes, I’m the only one who will eat the result!). I rarely use recipes any more; or, if I do, I use them just want to find out what the chef originally intended. Then, I put it away and try different variations.

Faculty & Curriculum Insight:

This week’s faculty reflection is from Mr. Evan Williams. Mr. Williams is our director of faculty & curriculum. He teaches five courses, is responsible for the overall architecture of Summit education, serves as a role model for Summit teachers, and cares for each and every Summit student through quarterly reviews and more. He graduated from Hillsdale College, earned an M.A. from Marquette University, and is pursuing a Ph.D. in Thomistic Studies at the University of St. Thomas. Mr. Williams and his wife Lauren have five children.

In the logic portion of my Introduction to Natural Science course, The Summit’s ninth-grade survey of the principles of natural science, I ask my students, “how many ways can two things be ‘like’ one another?” The question is abstract and consequently doesn't get much traction, so I usually follow up with examples. “Let's compare the squirrel outside with this black marker.” “They are both smaller than my backpack,” says a student seated near the front of the class.

After a pause, another student raises his hand and says, “they are both heavier than this pencil.” “Good. Now, let’s try to think of non-quantifiable similarities.” A longer pause, and then, “they both have multiple colors.” Fast-forward and we’ve usually composed a list of various other similarities. “They are both on campus, opaque, solid, etc.” I quickly add to this list, “they are both presently extant. They are each one of their kind. They are not bologna sandwiches, nor everything else which they are not. They are intelligible. They are signified with words. They came to exist from prior causes.” And so on.

The moral of the story is that two things can be ‘like,’ one another in a virtually infinite number of ways, most of which are trivial in a given line of inquiry. When someone compares two things, therefore, we should pay close attention and ask how they are similar before evaluating whether the comparison is relevant or sound.

I've noticed more and more that this lesson is lost in much of public discourse. Consider the phenomenon, ubiquitous in panel discussions on major news networks: someone makes a comparative claim and another responds by insisting that the two things being compared are not the same. This counterclaim is usually enough to run out the clock of the discussion, forcing the one making the comparison to backpedal and give ostensibly embarrassing concessions.

This rhetorical trick is really just a sub-species of “straw-manning,” but it's common enough in public discourse that I believe it deserves its own title. I call it, “the fallacy of imputed identity.” Here's how it works:

Person A compares X and Y and Person B responds by denying that X and Y are the same. B insinuates that A intends for the comparison of X and Y to be a claim of identity, which would make nearly all comparative claims absurd. When A explicitly qualifies the original comparison, B declares that A has conceded the falsity of his position.

For instance:

A: “Gossip is like assault.”

(Implied, let's suppose: “inasmuch as the former harms a reputation and the latter harms a person’s body”)

B: “Gossip is not the same as assault. Gossips aren't necessarily violent.”

(Implied: “gossip is not identical to assault”)

A: “Well, no. Of course they're different.”

B: “Then don't say they're the same! That's wrong and offensive.”

It is, of course, unreasonable for B to accuse A of absurdity without asking for further explanation. A's statement is underdetermined given the possible meanings of “like.” The unreasonableness of B is compounded when we consider the following: when someone makes a comparative claim they are almost never making a claim of strong identity. Excluding logicians, almost no one has in mind the conditions under which a thing is identical to itself. Given the extreme scarcity of such intentions in ordinary discourse, B's insinuation of identity is even more unreasonable. Virtually all comparative claims work across shared elements or aspects of things.

I propose to my students that we should accept a more limited meaning of ‘like,’ as default in public discourse. I encourage them to be attentive so that they can catch their rhetorical opponents committing the “fallacy of imputed identity,” and avoid the temptation to do it themselves. All things considered, this is, of course, a fairly minor problem. Still, every little bit helps to make straight the path to much-needed, reasoned discussion.

What I’m Reading Now:

“Classical Schools in Modern America,” originally published in 2019, remains a relevant essay for all those interested in the classical-education movement. The article was written by Ian Lindquist, a remarkable scholar, husband, and father who died of leukemia in 2022. Ian was a champion of this burgeoning movement, and few people did more to give it intellectual support at a national level.

Over the weekend, I read Who Not How, one of the books Mr. Burke brought for students, and it’s a great read. It argues that we are more successful if we ask “Who will help me solve this problem?” rather than “How will I solve this problem?” This is a great insight for reframing challenges, whether in the workplace, in your community, or even at home. Finding the right people and then giving them the freedom to solve problems is important for building and preserving good culture.

If you are enjoying this newsletter, please consider subscribing via the button above and sending it along to others who might be interested. Revenue from paid subscriptions will support The Summit Academy of Central Virginia.